By Madan Mohanka, PGP 1967

Caption: Tega factory in South Africa

I believe attaining Industry 5.0 Vision for organisational resilience and sustainability, through literature, films and stories, is both timely and relevant in today’s rapidly changing business environment. As we move beyond the ‘automation-driven Industry 4.0’ to a ‘human-centric Industry 5.0’, the focus shifts from mere technological advancements to harmonising intelligent systems with human creativity, ethical decision-making, and sustainable business models. The ability of organisations to adapt, innovate, and lead with responsibility will define their long-term success.

In Business Schools we need to make teaching more meaningful and engaging. It is important to explain ideas and theories with the help of other media, namely literature and films rather than by talking about EBITDA, supply chain or something suitably boring.

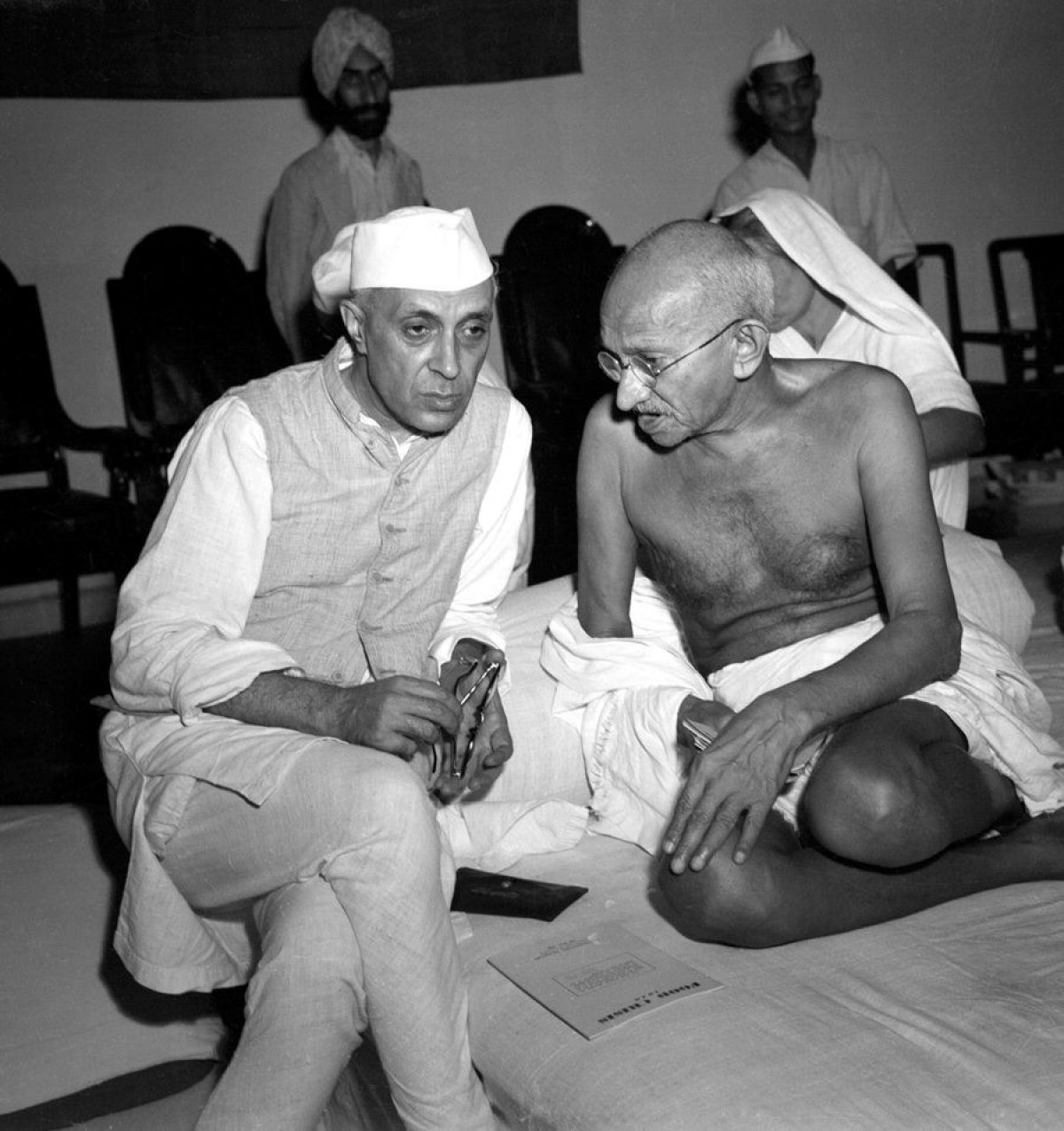

Caption: Gandhi and Nehru discussing at a Congress meet.

Management is not just about spreadsheets and strategy decks; it is about understanding people, making decisions and occasionally trying not to lose one’s sanity while doing both. And where better to learn these skills other than in stories where people make questionable decisions all the time, yet somehow end up teaching us something valuable?

For example, let us take strategy. If one were to say “Strategy is a planned course of action, designed to achieve specific goals” – it will bore you and not hold your attention. But if we relate business strategies to Gandhiji’s strategy of non-violence, the comparison of the two may come as a surprise and hold your attention. With the wisdom of experience, Gandhiji realised that our going to war with Britain would result in defeat. So he chose non-violence as a strategy to defeat the enemy, and Britain had no choice but to give in, resulting in the Independence of India.

Let us take leadership, for instance. How does one actually become a great leader? You could spend years in a classroom learning about a good leader’s attributes, or you could just watch Lagaan. Bhuvan, a simple villager, built a cricket team by bringing together a group of reluctant farmers who had never held a bat before and he led them to victory against a professional British team. Isn’t that leadership under pressure?

Bhuvan persuades, motivates, strategies, and even deals with office politics (because, let’s be honest, half his team wanted to quit multiple times). If you ever have to manage a difficult team, just remember: If Bhuvan could teach Kachra how to spin, you can teach your colleagues how to meet a deadline.

Allow me to relate another example. When I started my company Tega, the idea was to sell a new concept, not a product. Replacing steel with rubber linings in the mining industry, to save time, reduce costs and improve production. My job was to educate customers on the potential of making a change, even before setting up a manufacturing unit.

For five long years, my team and I spent an average of 25 days a month travelling by train to coal fields and mining towns, sleeping in railway rest rooms for lack of funds, to meet prospective customers. After receiving highly encouraging feedback from them, one of whom assured us our ideas would sell like “hot cakes,”we prepared three marketing potential reports – one by us, one by Skega our Swedish collaborator and a third by the Merchant Banking department of Grindlays Bank.

After setting up the plant, the very same people who had been so encouraging about its potential, refused to invest in our products. The mistake we made was that we assessed the potential but not the convertible potential. We had ignored the buying process of our customers, who were all in the public sector and were unwilling to risk their jobs by adopting a new concept.

After setting up the factory, faced with zero orders, we were on the edge of bankruptcy. I contemplated suicide but better sense prevailed and I sold my personal assets to pay the salaries of my loyal team members, who broke their backs in order to save the company. Eventually, we targeted a small fraction of buyers, concentrating our efforts on convincing them to make a change, and dragged ourselves out of penury. Today, Tega has seven plants in India, three outside India employing 450 expatriates in 18 countries and is one of the most diversified Indian multinational companies.

The lessons learnt were first, understand the importance of the convertible potential of any new business before investing and second, persevere even if the future looks bleak if you believe in yourself and your business idea.

Whoever has heard my story, has been careful to work out their own convertible potential, saving themselves from humiliation and loss. If I had explained the concept of convertible potential in any other way, they may not have remembered its importance. A meaningful story makes teaching far more effective.

Caption: A still from Pather Panchali

A perfect example of the importance of perseverance appears in Satyajit Ray’s film Pather Panchali (written by Bibhuti Bhushan Bandyopadhyay). The story of Apu and his family is a testament to perseverance despite crushing poverty and hardship. Apu’s relentless pursuit of education and his dreams, despite immense personal loss, reminds us that setbacks are just stepping stones to success. If Apu could rise above his circumstances and chase his ambitions, you can certainly rewrite that business proposal after a failed pitch.

Of course, literature also offers business wisdom, often hidden in unlikely places. Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice reminds us of the importance of ethical contracts, unless you want to end up like Antonio, promising a “pound of flesh” without reading the fine print.

George Orwell’s Animal Farm teaches us about power structures, leadership gone wrong, and why you should never trust a leader who says, “Trust me.” And if you ever need a lesson in ambition, read Macbeth – just remember, there’s a fine line between ambition and completely losing your mind.

Case writing and discussion as followed by IIMA is the best method of teaching management. It not only enhances the analytical and communication skills of students but also prepares future leaders for the complexities of a globalised market. I have personally collaborated with IIMA to contribute 15 case studies based on my experiences while building my company, out of which I believe 7 have been accepted by the Harvard Business School.

Madan Mohanka is Chairman and Founder of Tega Industries. He has published two books, ‘Professor Extraordinaire’ about his mentor Prof DVL Mote and ‘I Did What I Had To Do’, a biography by Anjana Duitt, tracing the history of Tega Industries. He lives in Kolkata and can be reached at madan.mohanka@tegaindustries.com