PROF LABDHI BHANDARI

REDISCOVERING PROF. LABDHI BHANDARI

By Apoorva Bhandari

On a crisp October morning, 33 years ago, a pall of gloom descended onto the IIM Ahmedabad campus. An Indian Airlines aircraft had crashed that morning near Ahmedabad airport and news filtered to the campus that one of their own, Prof. Labdhi R Bhandari, had perished in the accident. Students remember the formidable Prof. MN Vora coming into the classroom with moist eyes and breaking down at the end of the class. Prof. Bhandari was only 40 years old when he died, but in two short decades he had built an exceptional career as a student, manager, researcher, professor, consultant and administrator. In the words of Prof. GR Kulkarni, IIM-A had lost one of its “finest jewels”. In the days ahead, a memorial appeared in the Times of India depicting a lamp that had been suddenly extinguished. It captured the emotion felt by many of his colleagues, friends and students: of a shining star violently extinguished in his prime. In this retrospective feature, I try to reconstruct his story.

COMING OF AGE AT IIM-A In early July 1965, a frail young fellow with a severe cold showed up at the door of Prof. Vasant Mote, the PGP Chairman. He had just arrived in Ahmedabad from Rajasthan to join the second batch of PGP students. At three weeks short of his 17th birthday, Labdhipat Raj Bhandari (LRB) was by far the youngest of the batch. Though armed with an incisive and mature intelligence, LRB came to IIM-A with a humanities education, barely any Mathematics background, an entirely Hindi-medium education, and little comfort with spoken English. In the face of the famously formidable PGP-1 curriculum of cases, readings, in-class interrogations and surprise tests, along with a sophisticated, English-speaking culture at IIM-A, he was soon at sea – both academically and socially. Determined to not give up, LRB started burning the midnight oil, working late into the night to digest and solve cases. The going was tough, but with supportive mentors and batchmates, and a tremendous amount of elbow grease, LRB slowly found his footing. He ended the semester, to his own surprise, with the only A in Marketing, and a new, deeper confidence.

It was a remarkable transformation that was witnessed by his Sociology Professor at Jodhpur University, KB Kothari, who had since joined the faculty at IIM-A. “To my surprise, I discovered that within 4 to 6 months at IIMA he was a completely transformed person with amazing levels of self-confidence, communication abilities and a very smart presentation of self in all encounters. In my life, I have never witnessed such a radical transformation of a student personality in a few months mainly due to teaching-learning engagement, and peer group interactions in and out of the classroom at IIMA.” The PGP1 experience would have a deep impact on LRB’s mindset and his beliefs about the foundation of excellence. He wrote about overcoming a belief he had imbibed from his friends and peers at university: that the intelligent do not need to work hard. Indeed, he writes of how people who worked hard were seen in a negative light in his peer group at Jodhpur University because it implied that they were not intelligent. His struggle-filled experience at IIM-A, however, drove home the value of hard work and of improving over time. In the language of modern psychology, this was a shift from a ‘fixed mindset’ to a ‘growth mindset’ and for LRB, this was at the heart of his transformation. Three years later, he would call IIM-A his ‘break’ in life.

LRB receiving his PGP diploma from Kasturbhai Lalbhai in 1967, ranked 5th in class. Vikram Sarabhai is also seen seated at the table.

SELLING SOAPS AT HINDUSTAN LEVER The transformed LRB made an immediate impact on Dr. Ranjan Banerjee, Personnel Director at Hindustan Levers during campus interviews. Making a rare exception to their 21+ age requirement, HLL made LRB an offer to join their prestigious management trainee programme. After two years spent in the field visiting stockists and kirana stores, selling products hands-on, and helping launch RIN as part of the famed Hindustan Lever management training, LRB joined the washing products group and led a cross-functional team developing and launching a new detergent version of Lux Flakes. A year later, he became the brand manager for HLL’s most profitable product, Surf detergent, just as competitor Swastik Oil Mills launched a concerted promotional attack on Surf’s leadership position. The marketing challenge that LRB and his HLL colleagues faced, along with their their response soon became the basis for the first case that LRB wrote for IIM-A, ‘Consumer Products Ltd’, co-authoring it with HLL Promotions Manager, Diwan Arun Nanda, PGP ’66 gold medalist.

LRB’s work with Surf earned him one of the fastest promotions at HLL, making him the youngest Senior Manager in the company as the Head of Market Research. It was this experience that gave him deep expertise in new product introduction, something for which he would later become highly sought-after as a consultant. Two of LRB’s best cases at IIMA – ‘Household Products Ltd (C) & (D)’ – capture the outlines of this rather interesting slice of history.

In his new role, LRB commissioned and assembled market data about all the bathing soaps available in the market, the market segments they catered to, and their brand image (to the annoyance of his boss who said “HLL is not a research organization”). It became obvious from this data that there was no soap targeted at the youth, in particular young girls, and there was a significant potential market in that gap. LRB shared his findings with Shunu Sen, who called a meeting of marketing and advertising colleagues at HLL and Lintas, and from that brainstorming session emerged the idea of the “freshness soap” to fill the market gap. Several test products and brands were created and tested (including those mentioned in the Household Product cases) before the winning formula of a green marbled soap, with lime perfume, and the iconic image of a bikini-clad Karen Lunel as a teen playing with abandon under a waterfall came together as Liril in 1974, two years after LRB moved on from HLL. Prof. JP Singh, who heard this story from LRB himself in 1984, remembers “Standing in the corridor outside Wing 10, overlooking Louis Kahn Plaza in the forenoon, Labdhi explained to me how Liril had been created following a textbook research methodology to identify an unoccupied space, and the qualitative associations with freshness. It was like the periodic table in Chemistry that led to the discovery of so many new elements”. While the advertising side of the Liril story is well known, the market research and marketing side of the story, and LRB’s role in it, remains to be told.

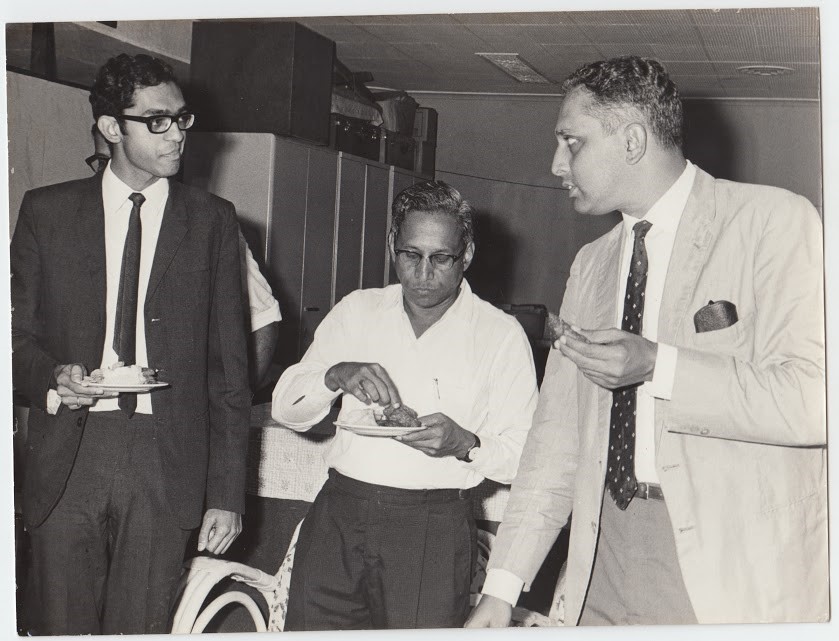

LRB (L) in conversation with Prof. John Camillus (R) in April 1970 at the first ever Alumni reunion. LRB was still working for Hindustan Lever at the time. 18 months later, he would join the IIM-A faculty.

FINDING MEANING IN ACADEMIA LRB was on the fast track for a very successful career at HLL with the company intent on sending him for a stint at Unilever headquarters. Indeed, it is very likely that he had been tagged as a ‘Lister’ – HLL jargon for the few individuals identified by the company early in their career to be groomed for the top job. But, LRB’s mind was in a churn. In a handwritten note, I found in his papers, he describes a feeling of dissatisfaction. He had stopped learning and missed the ‘science of management.’ He realized working in a corporate role “ran the risk of narrowing one’s vision, ambitions and values.” He also noted that “during the last few years my own awareness of ‘life’ around me – beyond my family and friends – has grown as has the appreciation of my ‘larger responsibilities’ to society.” He was looking for something more meaningful to do where he could “apply one’s mind and knowledge and have the satisfaction of fulfilling one’s larger responsibilities.” LRB had shared his thoughts with Prof. Ravi J Mathai, IIM-A Director then, who encouraged him to join the institute’s faculty. After mulling his choices over six months, and against the counsel of his friends and family, he decided to take the plunge. After four and a half very successful years at HLL, LRB put in his papers to the shock of his mentors and colleagues at the company. Incredibly, he turned this life experience also into a case for the OB area – Deepak Dey’s Diary, which brings out, quite beautifully, the chaotic, rambling, semi-rational and semi-emotional churn that goes into making personal decisions.

On the cusp of his transition from HLL to IIM Ahmedabad, on the 30th of December, 1971, LRB would hear the sad news of the unexpected passing of Dr. Vikram Sarabhai, the visionary moving spirit behind IIM-A. LRB would join the institute on the 3rd of January 1972. Three days later, he would be joined by another young Turk who had gone through a similar psychological churn – CK Prahalad. That very month, on the 25th of January 1972, Ravi J. Mathai, the celebrated Director of IIM Ahmedabad, and the man who had attracted LRB and CKP to the institute, would drop a bombshell in the first faculty meeting of the year – he would be voluntarily stepping down from his position. The IIM-A torch was gently being passed to a new generation.

In a few months, LRB was off to Columbia University where his research focused on social marketing. Conducting field research in the villages of Rajasthan, he wrote an award-winning dissertation that offered novel methods for developing communication appeals for family planning programs. Ironically, when he returned to the faculty of IIM-A in April 1976, India was in the throes of the Emergency during which ‘family planning’ had turned into a sinister programme of compulsory, coercive ‘sterilization’. The excesses of the Emergency destroyed India’s family planning programs and with them, any hopes LRB had of continuing his award-winning research in the area.

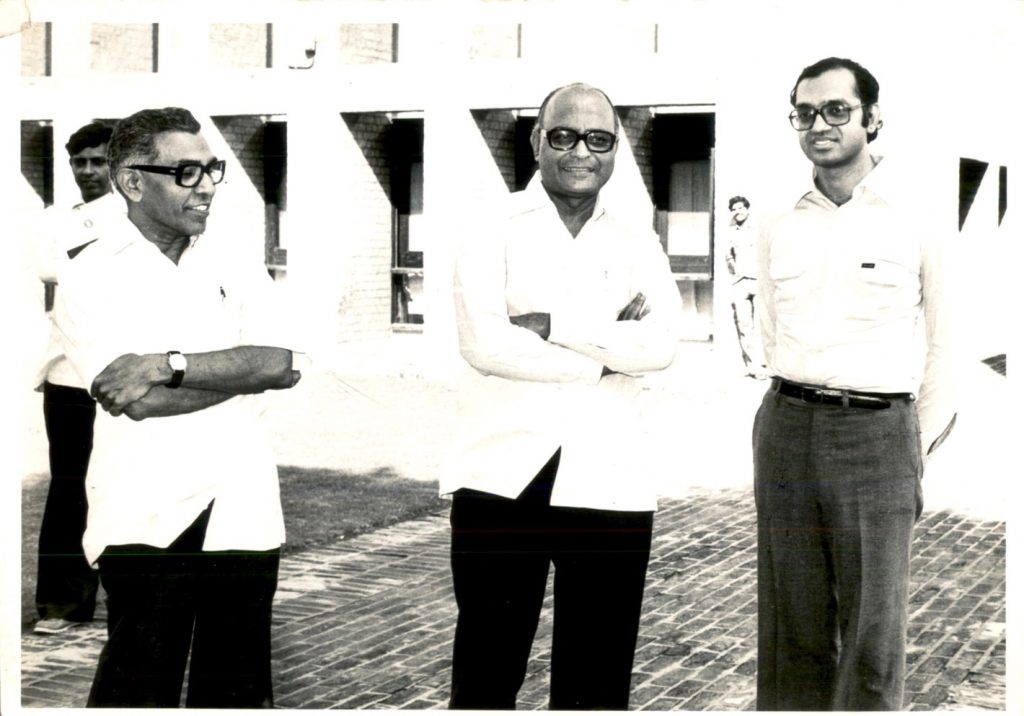

LRB (R) with two IIM-A Directors. Dr. IG Patel (M) and Prof. NR Sheth (L). This was on the occasion of the visit of Governor BK Nehru to the campus in 1984 in connection with the first Advanced Management Programme (AMP) for public sector executives that LRB organized as Chairman of Management Development Programmes.

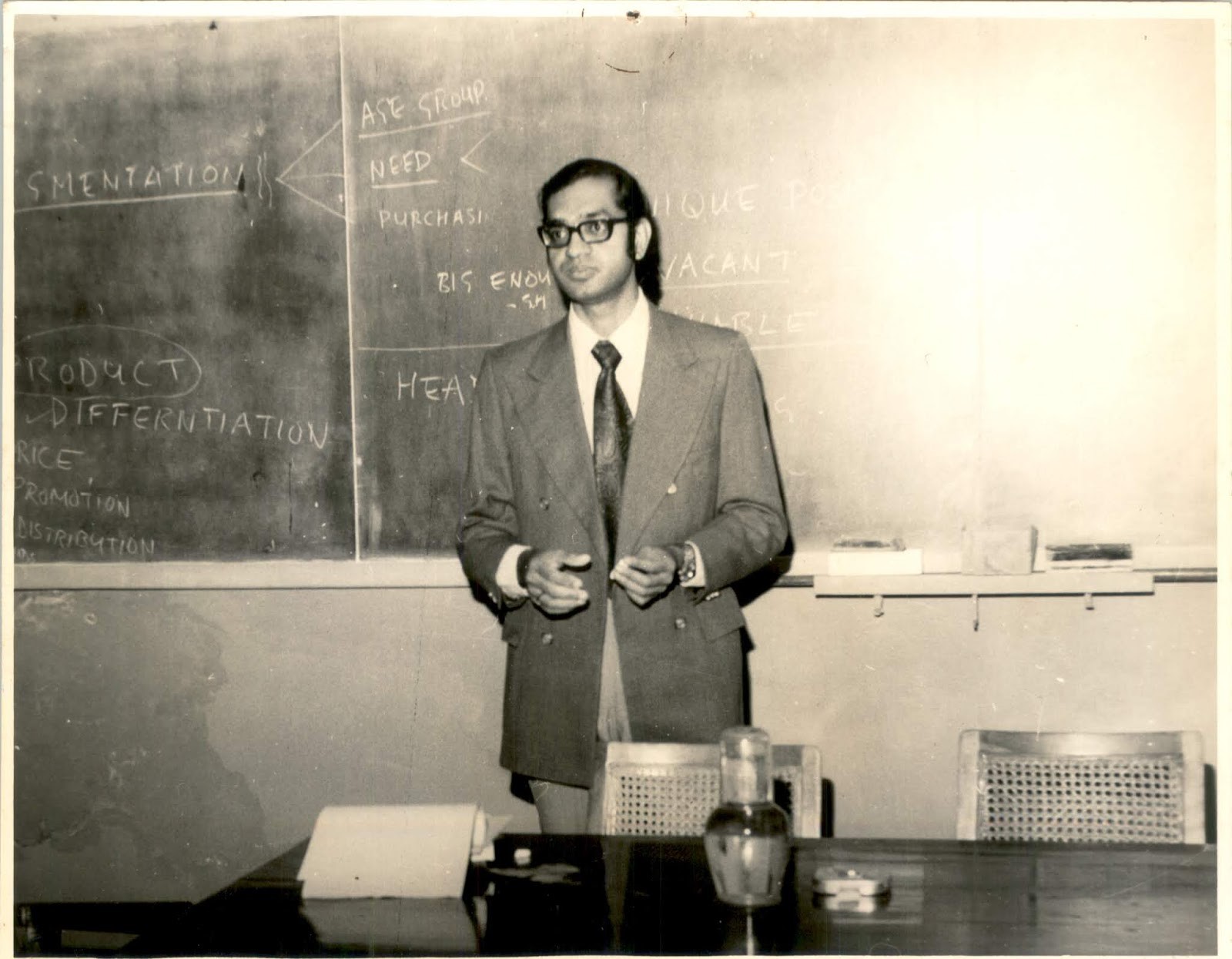

IN THE CLASSROOM It’s hard to paint a picture of what LRB’s classes were like, never having experienced one first hand, especially for a readership that includes many of his former students. Thankfully, many of his students have clear memories of his incisive classes even after four decades have passed and so I can try to give a flavor.

LRB’s classes always used the case method. And like most case teaching at IIM-A, his teaching style was Socratic, asking questions, prodding with “So?” and “Why?”, and challenging your answers to help you synthesize and defend careful solutions to the practical business problems that the case presented. He would set the tone right from the beginning: Rajnish Agarwal, PGP ‘88 recalls his very first class, “Labdhi walked in. We sat huddled together, partly in fear of his reputation and partly in awe, overwhelmed I think with his presence and his serious demeanor. After a few pregnant minutes of uneasy silence, Labdhi said, ‘So, what should Mr. Shah do?’ We all looked at each other for the ‘sacrificial one’. He then repeated, ‘Has anyone read the case?’ … to which a brave one amongst us, at the very back of the class, sat up and said “Sir, would it not be better if you introduced yourself to us first?….Labdhi, composure personified, looked at him and said ‘Would that help solve the case?”

Otherwise soft spoken, LRB adopted a very tough persona in the classroom. As early as 1972, as a rookie Assistant Professor without a PhD, LRB would walk out of the classroom if his students hadn’t read the case. As Pranesh Mishra, PGP ’79 remembers: “One would be a fool to attend his class without reading the case in advance. He would pick students at random and ask for a point of view and God help you if you were unprepared.” Students remember searing roasts of those who made the mistake of trying to engage in arbitrary or generic CP. To a student who said something like “The product doesn’t have an identity”, LRB would fix a glare before responding, “You mean it’s not carrying an identity card”. To someone who said, “I will survey the market” and didn’t say more….”How?? By climbing up an electric pole.” Delivered in his quiet, unassuming manner, these roasts were devastating and quickly set the tone and culture of the classroom. An unnamed PGP-2 is quoted in 1986 in the campus student magazine as telling a rookie PGP-1 “Don’t make arbit CP. He will chew you.”

His elective courses were always heavily oversubscribed. His classes, often scheduled post-lunch, would always be full – with those not taking the course (and during cultural festival, even those visiting from other campuses) coming to watch the gladiatorial spectator sport. As S. Ramanthan remembers: “His acutely economic expressions were sufficient to punch holes in the collective verbiage churned out by the class and Labdhi intervened at the right time to sum up the case, leaving Dr. Watsons wondering why they could not think on those lines. The next class we were better equipped or so we thought and Labdhi took the logical combat to a higher level and the story repeated.’

LRB’s goal as a teacher was not just to impart marketing knowledge but to prepare students for the tough world of business by shaping their thinking, beliefs and values. He created a classroom environment in which the students could not fly by the seat of their pants. They had to put in the hard hours and rely on careful thought and preparation, rather than just on smarts. And, to this end, he consciously cultivated a classroom persona that was made-to-order. Everything he said or did clearly signaled that he meant business. He was very serious in his demeanor and seldom smiled. He deployed his dry humour and acerbic wit to punish anything that betrayed looseness or a lazy approach. As Piyush Jindal, PGP ’82 recently said: “No fluff. No generalizations.” As they engaged in this arms race of logical combat, without even realizing, their minds were being carefully chiseled.

A BUSY CONSULTANT LRB’s incisive mind, lucid articulation, unassuming manner, and an unusual combination of deep academic insight and practical business experience made him a highly sought-after consultant. His client list was long and wide-ranged, from public sector companies like the Cement Corporation of India, SAIL and SBI, MNCs like Cadbury, Citibank and HLL, and domestic concerns like Enfield, ITC, EID Parry and Bombay Oil Industries, to name a few. Two stories paint a picture.

Jerry Rao, then in charge of Citibank’s consumer business in India, gives us a flavor of what it was like to work with him. “Citibank was planning on entering the Credit Card Business. I was looking for a good consultant to help us understand whether there was a real business proposition and as to how best we could grapple with it. We managed to persuade Labdhi that our project was an interesting one and he made time for us. In engaging with Labdhi through the project, what stood out was his soft personality, his razor-sharp and incisive mind, his willingness to separate tentative conclusions from firm ones and go in search of data to strengthen the tentative results and above all his characteristic ability to combine solid theoretical insights with practical business applications. I have worked with many consultants including quite a few from the best-known consulting firms in the world. Working with Labdhi beat all those experiences hands-down. The project was a success in virtually every way. In retrospect, it is so clear that Labdhi asked the right questions and his analytical insights were spot on. The Citibank Credit Card Business in India went on to become a first mover, a pioneer and a market leader.”

But LRB did not just work with large, glamorous companies. Harsh Mariwala of Marico tells us of their association: “I was part of the Bombay Oil Industries, which was a typical family-run firm selling largely unbranded products like hair oil. I wanted to start branding our products but we had no in-house knowledge/expertise of marketing and as a small company located in the midst of Bombay’s commodity markets, it was hard to attract professional talent. I had no formal management education and through many 1-on-1 sessions, Labdhi pretty much gave me my first exposure to the entire field of marketing – how to position a product, market research, segmentation, brand building, etc. We must have spent about a total of 15-20 days together in the early 80s. From our interactions, it was clear that he was very bright – extremely sharp. He was also very, very hard working. I remember he used to be very busy during that period and would not have time to meet when he was in Mumbai. So, often, I would meet him at the airport, catch the flight with him to Ahmedabad and we would work all night and then I’d catch the flight back to Mumbai in the morning! That was the sort of inner drive he had to excel.”

LRB (R) and friends in the lawn of LRB’s home (no. 316 IIMA Campus), likely on the occasion of his son’s birthday. From Left to Right: Dilip Thaker, one of LRB’s closest friends and PGP batchmate, then an executive at IBM London, Prof. Sasi Misra, Prof. Abhinandan Jain, Mr. Govind Baldava, another PGP batchmate.

LRB (2nd from right) receiving a memento from a student in the company of two other IIM-A stalwarts – Prof. MN Vora (2nd from left) and Prof. Abhinandan Jain (right).

EPILOGUE LRB’s tragic demise cut short a brilliant career that had many more achievements on the anvil and much to offer to the world. One can only speculate about the fame and fortune that awaited LRB in the post-liberalization economy as issues of marketing and competition became center stage. Perhaps, in the years to come, he would finally have given in to his entrepreneurial itch to build a business, as he sometimes expressed to his family. Others say that had he not died in the accident, he would have “outranked the likes of several latter-day global management gurus.”.

More concretely, LRB would most certainly have been appointed the next Director of IIM-A in 1989. According to Dr. V Krishnamurthy, then Chairman of the IIMA Board of Governors, LRB’s name was on the top of the list, having been put forward very prominently by both faculty and alumni. Indeed, LRB had already been sounded out about his likely appointment – he had told his wife to prepare for the impending house move, and on the night before his death, he had talked at length about what his vision would be as IIM-A Director with his friend Shyam Sunder Suri (PGP ’72). As his close friend, neighbor and colleague, Prof. Abhinandan Jain recently said in an interview, “He was the best person to do something in academic administration.”

Whatever the future may have held, LRB would have remained his humble, unassuming self. As S Ramachander pointed out in a thoughtful obituary, “Labdhi remained consistently unflustered by the attention and the glamour of the multinational marketing world. He never bothered to conceal his Marwari roots and cultural origins in semi-urban Rajasthan. He was very conscious of the fact that he was – and wished to be – a simple person, all of a piece.”

To learn more about Prof. Labdhi Bhandari, please visit the Reconstructing LRB project at www.labdhibhandari.org. If you would like to share memories or stories about Prof. Bhandari, please write to editor@labdhibhandari.org

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.