The former WWF-India CEO reflects on a career spent in the development sector

Dilnavaz Sam Variava (formerly Sidhwa) PGP 66

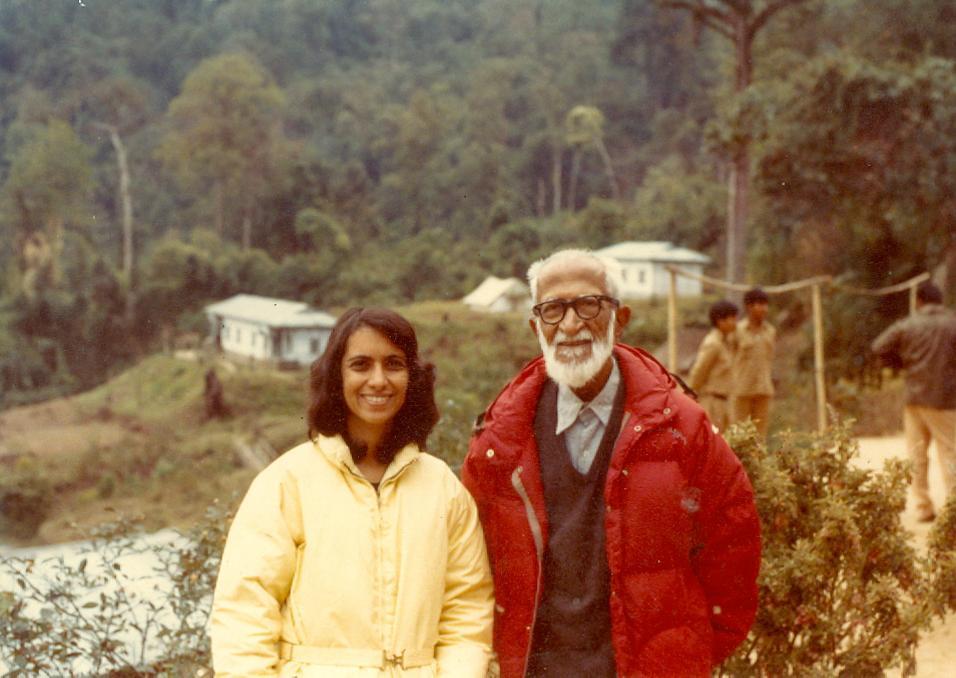

Caption: Dilnavaz with Dr Salim Ali (India’s foremost Ornithologist) on a BNHS expedition in the Namdapha forests, Arunachal Pradesh

I once asked the Dalai Lama, “What is the purpose of life?” I expected a profoundly enlightening answer. The erstwhile monarch of Tibet, now just a monk, loved and revered across the world, gave a simple and sensible answer, “To be happy. Isn’t that what everyone wants?” Yes, indeed. My own happiness has come from good relationships, from nature’s wonders, from “having enough” and from being able to give to others.

I joined IIMA’s first batch in 1964. From 1966 to 1973 I worked in industry, resigning as Director of Personnel & Administration of Grindwell Norton Ltd, India’s first grinding wheel company, when my son was born. I wanted balance in my life, and not just a career. I decided to use managerial skills for a social cause. Fortunately, just then, Ravi Matthai was asked whether he could suggest any IIMA alumnus as CEO for World Wildlife Fund (WWF)-India. Ravi replied “Only one” and he named me. Perhaps it was because I took care of a stray dog on the campus? Environmental conservation was unknown at that time, so it took time to convince me that healthy ecosystems are the foundation for well-being – even of humans. That’s how I accepted the stint at the age of 29–part time, flexi-time, poor paying but life-enriching work.

Discovering conservation and making WWF India sustainable

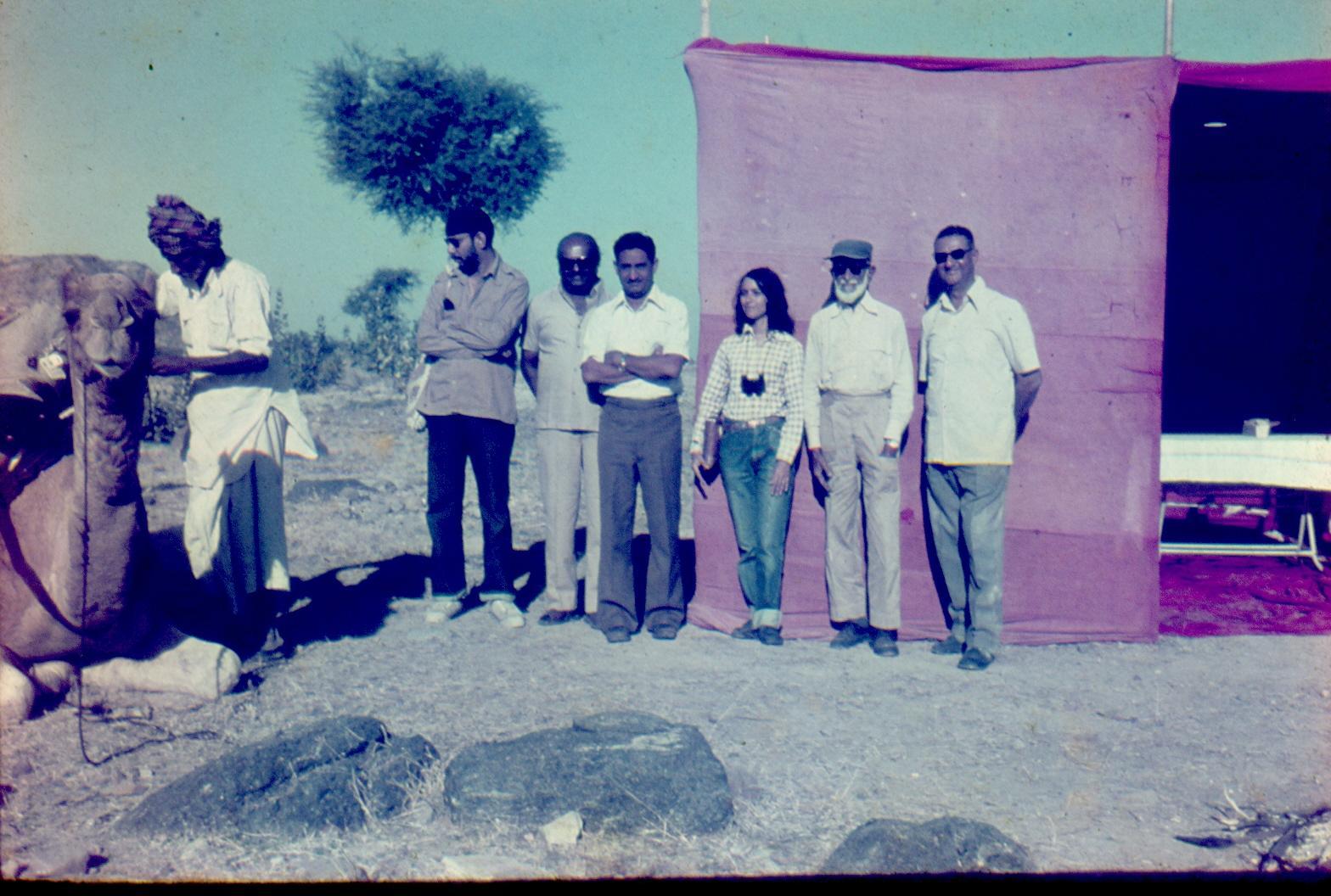

Caption: On a BNHS expedition in search of the breeding ground of Lesser Flamingos in the Great Rann of Kutch, Gujarat

I discovered the WWF-India office was just a corner of the Bombay Natural History Society’s library, with one executive assistant, one peon and one part time secretary. A far cry from being a Director in an MNC! The Trustees were an impressive lot – Maharaja Fatehsinghrao Gaekwad of Baroda (President), Holck Larsen (Chairman of Larsen & Toubro), Sumant Moolgaonkar (Managing Director of Tata Motors), Sohrabji Godrej (Chairman of Godrej group), Vasant Rajadhyaksha (former chairman of HUL and Member Planning Commission), along with active conservationists Duleep Matthai, Anne Wright, Zafar Futehally. They left me largely to chart my own course. Most people in 1973 were ignorant about environmental conservation. I decided to change that by convincing editor after editor to cover environmental concerns. When the Emergency was declared, and political news dried up, editors started chasing me for news! Project Tiger was launched in April 1973 and WWF International raised a million dollars for it. WWF-India coordinated this donation. The Nature Clubs of India was launched and some important projects were supported. But funding was erratic and insufficient for growth. I felt financial sustainability was important and set up a Products Department, with greeting cards and calendars. IIMA education was useful – and we rapidly covered all staff costs and more.

Back to business world and BNHS

Caption: At Bharat Floorings’ Centenary Exhibition

In 1976, I resigned. My father had died and my mother was struggling with a loss-making family tile business. I took charge of its warehousing division, continued as non-executive Director of Grindwell and eventually also turned around the loss-making tile business. But I always kept time for social work. On the persuasion of Dr Salim Ali, President of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), I joined its Executive Committee. We had become good friends during my WWF days, I relied on his natural history knowledge and he on my administrative help. For the next 10 years, I made memorable trips, from Bharatpur to Bandipur and from the salt deserts of Kutch to the rain forests of Arunachal, with one of the world’s leading ornithologists and other BNHS experts.

But BNHS was not all fun. The BNHS Committee was a dedicated lot, but fiercely divided! I could help bridge the differences and became its longest serving Vice President. Here again I built up a Products Department to ensure core staff salaries were sustainably financed, and helped set up the Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology & Natural History as a separate organisation with government funding. It was soon taken over by the Government, which I had feared would happen if BNHS took government funding.

From Advocacy to Agriculture

During my BNHS days I was nominated to various apex GOI Committees – the National Committee for Environmental Planning & Coordination, the National Board for Wildlife, the National Conservation Strategy Committee and a Planning Commission Committee. The latter two were at Dr M S Swaminathan’s initiative. When he was Secretary Agriculture, Govt of India, I had met him at a seminar where I presented a paper on saving the ecologically rich ‘Silent Valley’ from a hydro project. Lobbying people across party lines, from Kerala Chief Minister Nayanar and Opposition leader E M S Namboodiripad to PMs Indira Gandhi and Charan Singh, our Mumbai committee had supported the initiatives in Kerala until Silent Valley was declared a National Park in 1984.

After 1987 I had ceased to play any activist role, as my husband had become a Judge. I was surprised when, in 2003, Dr Swaminathan asked me to chair a Working Group on the Ecological Foundations for Sustainable Agriculture in Maharashtra. I put together a committee of experts, myself being the least expert of all, and our recommendations were accepted. This was a turning point in my honorary work. Visiting Vidarbha, the suicide capital for farmers in India, we got no reports of organic farmers committing suicide due to agricultural distress. Self-reliant, they were free of the loan-based high-cost-high-risk agriculture of chemical farmers, who experienced deep distress if the monsoon or market prices failed.

Genetic Modification of crops, e.g. Bt Cotton, claimed to provide higher yields, lower pesticide costs and higher profits. Intrigued, I studied their global and Indian performance. The claims were largely propaganda. Genes were inserted in the highest yielding hybrid seeds, but non GM seeds could give the same or higher yields under similar conditions. Pesticide use was reduced for bollworms in Bt cotton, but increased for sucking pests. Globally, 87% of GM crops are herbicide tolerant, and the Courts in the US have now awarded billions of dollars in damages to cancer victims of glyphosate herbicide. In India, Bt Cotton farmers continued to commit suicide. I saw that organic or natural farming provided a sustainable approach to the wellbeing of people and the environment.

Efforts to fight Anaemia

Caption: At a 2019 gathering of Anaemia Free India Forum initiated by The Sahayak Trust

As Chair of the Rural Development Committee of the Rotary Club of Bombay I supported NGOs promoting organic farming, but few farmers would leave dependency on chemicals. Women, however, readily adopted organic kitchen gardens, and doctors reported a reduction in anaemia. So in 2016, at the age of 72, I made this the new focus of The Sahayak Trust which I had founded decades earlier. We initiated an Anaemia Free India Forum with 16 NGOs. Capacity building is presently being provided to over 600 NGOs who are working in 6500 villages across 7 States. According to their reports they, in turn, have provided training to 5999 schools, 4036 anganwadis and 10,725 women self help groups. Collectively over 60,000 organic kitchen gardens for nutrition (OKGNs) have reportedly been created, resulting in better nutrition, better health and an estimated Rs 21 crores of vegetables consumed. An OKGN can cost just Rs 150 per annum with family labour and meets several UN Sustainable Development Goals.

My journey is not unique, commitment to social contribution has always been our family value. My sister, Almitra Patel, an engineer from MIT, works honorarily on solid waste issues. We both ascribe our inclination for socially meaningful work to our parents. In 1922, our father, inspired by Gandhiji’s Swadeshi movement, took a loan to start The Bharat Flooring Tile Company. In 1949 our parents took over a school of 40 children that was closing down. The school now has 3,800 low-income children from 20 villages. Giving back to society, and the concept of the trusteeship of wealth, was thus a message conveyed by our parents through both words and actions. It has been personally enriching and I hope many IIMA alumni will one day come to that moment, when they too say to themselves, “I have enough. What can I give, and to whom?” It’s never too early – or too late!

Dilnavaz Sam Variava lives in Mumbai and is Managing Trustee of The Sahayak Trust and President of the Sarasvati Education Society. She can be reached at dsvariava@gmail.com.