AN INSIDER’S PERSPECTIVE OF THE CORONAVIRUS VACCINE DEVELOPMENT

Beheruz N Sethna (PGP 1973)

Unless you are an anti-vaxxer or a COVID-denier, you have probably been vaccinated against COVID, and perhaps have had booster shots as well. You know the vaccine to be safe, you know that, if you take it, your body won’t get magnetized and you won’t grow a third leg or arm. You also know that the risks are minimal and the benefits are considerable.

But, how do we know all that? Because we have evidence of vaccine trials. We have the results of perhaps the largest scientific experiment of our times.

That’s a loaded word (‘experiment’) I used. Please forgive me if I get ‘geeky’ or technical for a moment while I set the stage for these vaccine tests.

Statisticians and indeed most managers know that correlation is not the same thing as causation or proof or causality. Two examples of correlational studies which were not experiments are shown below:

1) When I was a student at Columbia University, I helped someone do a study of violent crime in New York City. (Historical digression: This was in the early 1970s when crime was a problem in NYC; things improved significantly later on.) We took advantage of the fact that NYC (at least, the newer parts of it) was constructed along a grid of avenues that ran North-South and streets that ran East-West), thus creating city blocks that yielded convenient units to sample. We could study the prevalence of violent crime in each city block and compare it with the prevalence of crime in another one close by. We also studied several other factors about each city block and tested if the prevalence of crime could be explained by any of them. In that process, we found that the number of supermarkets in a city block was significantly correlated with the amount of crime!

Now, that doesn’t make any sense. No youth with nothing better to do would suddenly get incensed with seeing multiple supermarkets and decide to hit or shoot someone. So, surely, the number of supermarkets does not cause violent crime. The reverse cannot be true either – no entrepreneur would say, “There’s a lot of violent crime here; let me build a supermarket!”

So, while there was a significant correlation between the number of supermarkets in a city block and the amount of violent crime, it was silly to imply that either one would cause the other.

Correlation is not causation. (I’ll leave you to puzzle out what was going on before I reveal the answer, but with the erudite audience of this magazine, I bet you figured it out immediately.)

2) There are findings from other studies that indicate that the amount of violent crime (apologies for yet another example involving violent crime) is significantly correlated with sales of ice cream!

Again, it does not seem reasonable to have someone say, “Boy, that was a great-tasting ice cream cone. Let me go hit someone or do grievous bodily harm to someone.”

Neither does it make sense for someone to hit someone or inflict grievous bodily harm, and then feel that he needs an ice cream cone to celebrate his illegal act.

So, while there is a significant correlation between ice cream sales and the amount of violent crime, it is ridiculous to suggest that either one would cause the other.

Have you figured out what was really going on? The answer is provided below. So, if you need time to figure this out, pause here, before you read the answer.

In each example, a third variable was the cause of both observed phenomena. The correlation between the two variables in each case study, while statistically significant, was an accidental finding. In the first example, it was the population density of the city block that led to more crime and more supermarkets. In the second example, it was hot weather/higher temperatures that led to more crime and more ice cream sales.

All this is simply to say that, if we want to test the real effect of a vaccine, and to prove conclusively that the vaccine is effective in preventing COVID, or not having bad effects (like falling ill, or death, or growing an extra limb, or one’s body getting magnetized), a correlational study like the ice cream or supermarket study will not suffice. You might see a correlation, but that is not good enough for a test of effectiveness when hundreds of thousands of lives are at stake.

So, we must abandon such correlational studies for such a purpose, and our experimental design must be an experiment.

WHAT IS AN EXPERIMENT? In its simplest form, it requires an experimental group (a group that receives a ‘treatment’ that you wish to test the effectiveness of) and a control group (a group that does not receive that ‘treatment’ but rather, receives a placebo instead). It also requires matched samples – meaning, the two groups should be reasonably matched in terms of demographic or health characteristics. In our example, health is relevant because you don’t want one group to be in particularly bad health or health-compromised in some way, relative to the other, because you won’t be able to study the effect of the treatment if that is so.

Further, the assignment of treatments (real vaccine vs. placebo) must be random and secret, meaning they cannot be known to the test subject or to the nurse or even to the Principal Investigator, so as to avoid all bias.

The reason why people all over the world were able to take vaccines to prevent the coronavirus in early 2021, without several hypothesized or hyped ill effects occurring, is that an experiment (not just a correlation study) had already been done with tens of thousands of people.

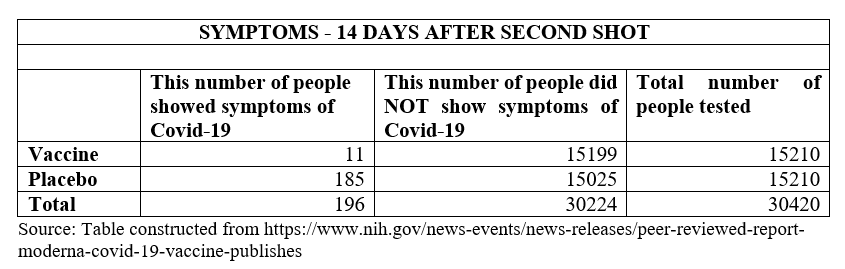

And, the results were compelling. The results shown below (‘Symptoms after second shot’) refer to a sample of about 30,000 participants in the Moderna vaccine trial. The link referenced below has lots of other data as well, including ‘Symptoms after first shot’ and ‘Severe Symptoms after second shot’.

I do not intend for this to be a statistics paper, so let me conclude this part of the account by saying simply, that the analysis of variance results was very, very significant and compelling. Of course, there were several other vaccine trials as well (such as Pfizer), and they showed excellent results as well.

NOW, LET US MOVE TO THE HUMAN SIDE OF THE STORY

We have seen how the public can be reassured of a vaccine’s effectiveness and of no severe side effects (like death or growing a third leg) based on vaccine trials with tens of thousands of subjects having taken the vaccines or placebos.

But, but, but …

From where do you get those tens of thousands of people to participate in these experiments? At the start of the vaccine trials, we do not have the safety track record that we had after the trials. So, people are taking their lives into their hands when they agree to participate in the vaccine trials.

So, how do you find these bakras, willing to participate before the test results are known? I will share my personal story here.

Digression: For several years, I have gone from my university in the US to Balgram, an orphanage school outside of Lonavala, to teach science to orphaned kids. In the US, we faculty members get paid our full salary for the academic year (August to the first week of May) and the summer is ours to do what we like. Most faculty teach in the summer for substantially extra money. I am a very popular guy in my department because, since I go to Balgram, I don’t compete for summer teaching money (as a senior professor I would get a substantial chunk of resources if I wanted). I willingly give up this increase in my bank balance in favor of the (presumably) increased Heavenly balance each time I teach at Balgram! But, in 2020 – since summer teaching decisions are made in January, before the pandemic, and Balgram went through a lockdown in April, I lost out on both.

So, I was sulking at home in the US, without either my spiritual or monetary bank balance, and then this idea came to me – I could volunteer to be a subject for the vaccine test!

At the age of 72 (and having had heart surgery), some of my family and friends thought I was nuts (not the first time that this thought has crossed their minds, and it won’t be the last time either) and others called it courageous, but I decided to be part of a COVID-19 vaccine trial.

In July, I contacted Emory University (about 50 miles away) and volunteered my services. They were delighted to get an ‘older’ guy in their sample. I went through an online screening at Emory and we had a lot of email conversations. Many of my friends cautioned me against going through with it because it was untested at that point, but I did take the plunge and went to Emory in August. There were many, many screening questions on medical history, past surgeries, medications, etc., blood was drawn for tests, I had a nasal swab done to determine whether I was already infected, then a final screening by the PI (Principal Investigator) physician, and then I was officially accepted into the trial.

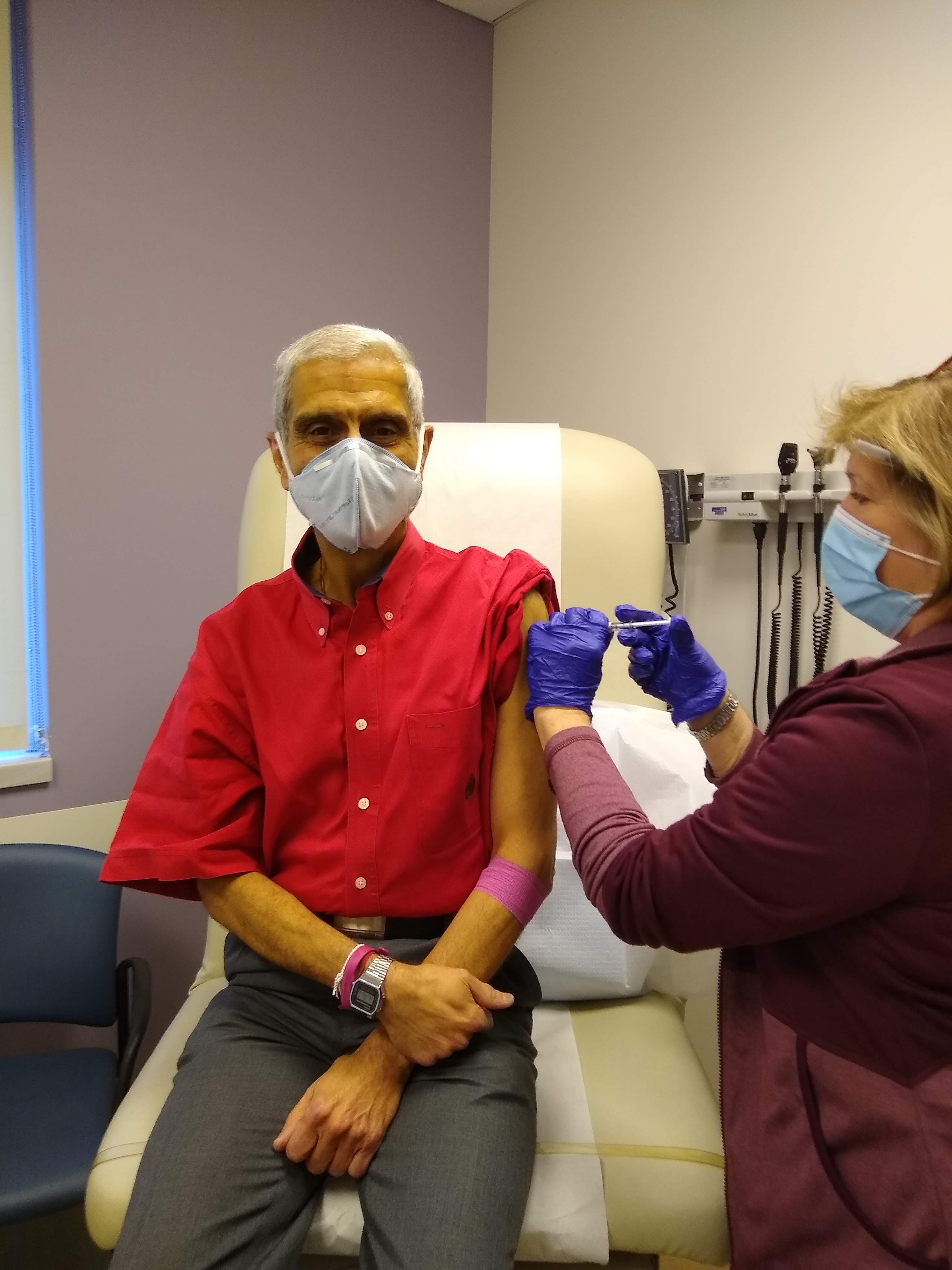

… and, 10 minutes later, I took my shot!

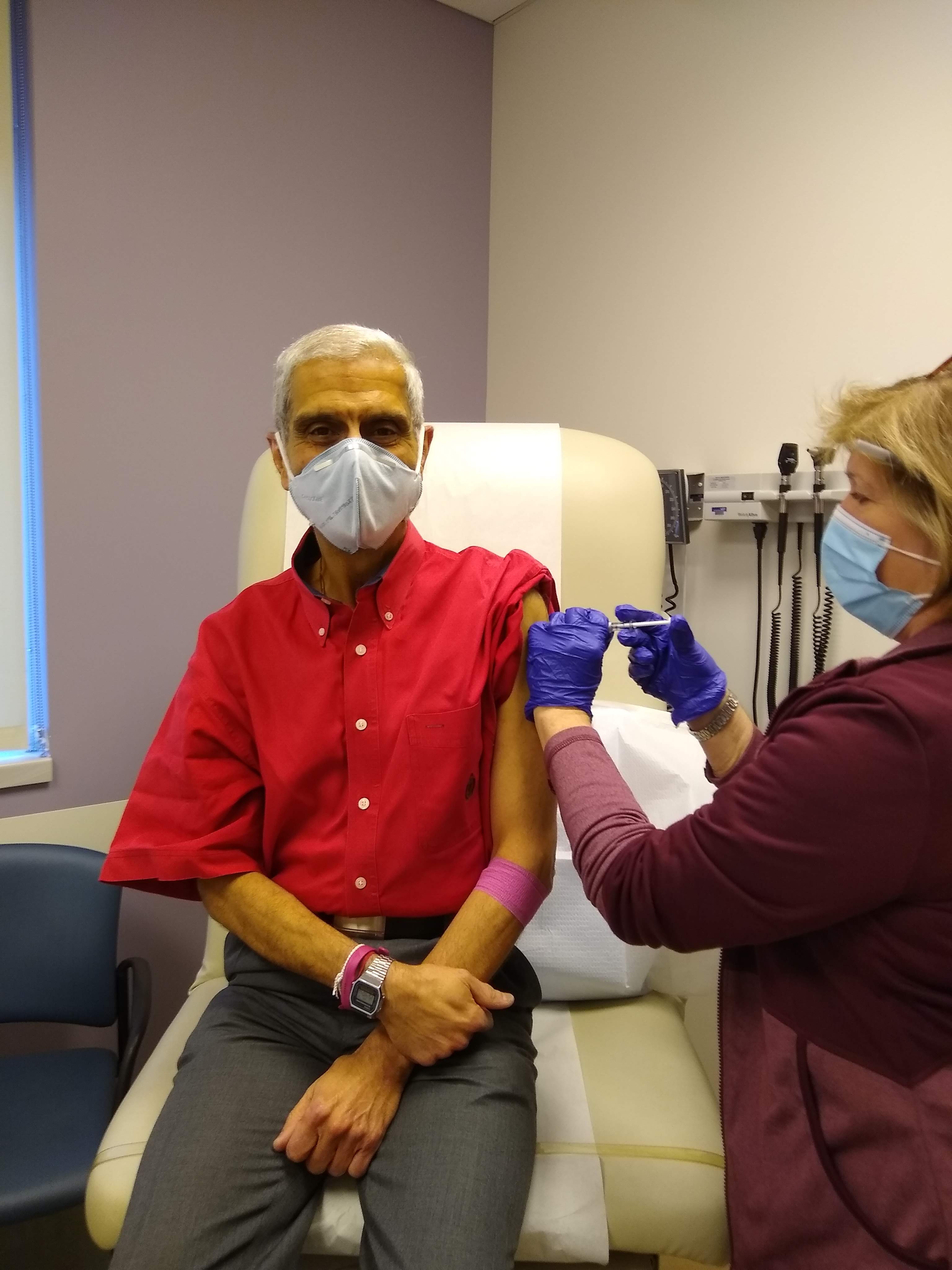

Ms Leisa Bower, the nurse at the centre, giving the shot to Mr Beheruz Sethna

It was a blind trial so I didn’t know if I got the placebo or real vaccine, but since I did not show any symptoms, I suspected that I got the placebo. This is a true random trial with randomized selection, so 50% of the sample gets the real vaccine and the other 50% gets a saline injection. I had to report to them on an app every night on about 15-20 questions about everything from pain at the injection site to serious symptoms.

As I wrote to a friend: “I am sulking a bit because I think I may be in the control group that got a saline shot, but I’ll feel better if I start feeling worse.” I didn’t.

A month later, I went again for another blood draw, nasal test, and a second vaccine shot – for which a much more severe reaction was expected. However, I did not have one, so I was now sure that I got the placebo. Then again after another month, I had to go for monitoring purposes, another blood draw and nasal test (but no more vaccine shots).

After the vaccine was approved, I was offered the opportunity to be ‘unblinded’ – I don’t think that this was a real word when we were at IIM half a century ago, but it is now. I did go for that option and found out that I had indeed received the placebo (no surprise there). After that, I was offered the vaccine and I took it.

I continued in the vaccine trial from July 2020 to October 2022, so that they could study longer-term effects, and several times, I drove 50 miles there and back, where they drew ‘gallons’ of blood (slight exaggeration) each time to study what happens in the longer term.

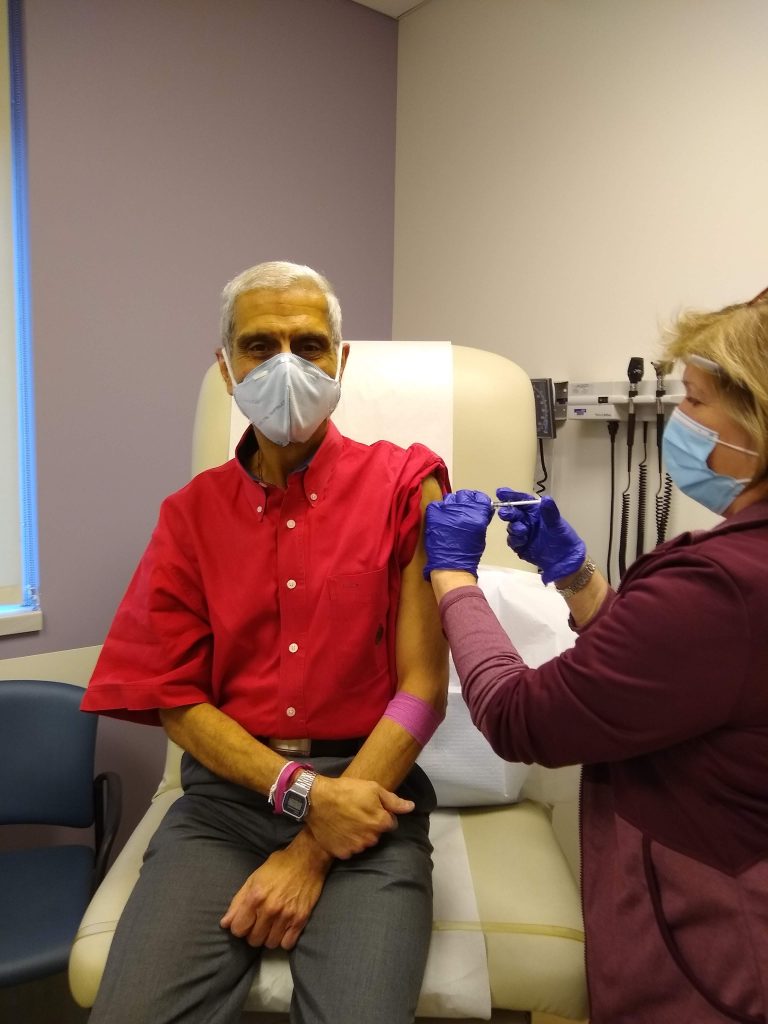

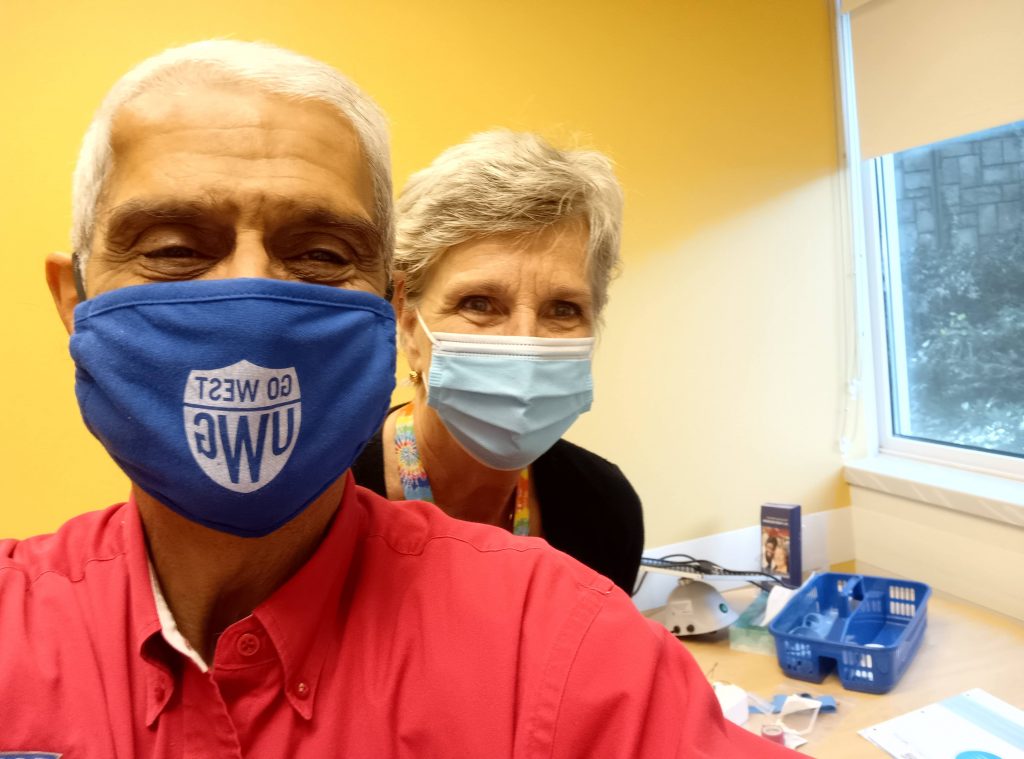

The end of the Covid-19 vaccine trial (July 2022 – October 2022). Mr Sethna with Ms Kathy Stephens, the nurse who was the in-charge of his case

So, that was my small part in the quest for the vaccine! This is a classic experimental design (causal research) which was fundamental to proving causality. (Moderna: Covid vaccine shows nearly 95% protection). I was honored to be a part of what I still believe to be the largest experimental sample of our times.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.